Mt. Taylor

Mt. Taylor

Mt. Taylor

Mt. Taylor"Grinding the clay is the hardest part. It's stone really, and then breaking up the old shards for temper. It has to be right, or the clay collapses--too soft, or stiffens--too hard" (--Rose Chino Garcia, Acoma potter).

My friend, Rose Chino Garcia, passed away on November 10, 2000, at the age of 72. Her daughter, Tena Garcia, is carrying on the tradition of this magnificent pottery, which she learned from her mother and grandmother, Marie Zieu Chino.

Remembering Rose At the edge of the mesa,

against the sun and the far rain,

she stood.

I can see her--small and distant

as the mountain, its wild buttes

enthralled by cloud,

the rain standing

silvered among them--

a child playing in the mud that sang,

among the shards that tempered her

and bound the clay

as ribbons in her hands.Rose tithed the clay, cast it to the fire,

knew the price her hands paid

changing rock to bread.

She ground it into color,

gold and rust and red,

boiling beeweed down to ink

fine as Earth's dark muddy crust.The mountain glowed.

Rose against it shone.(©12/16/00 Carol Snyder Halberstadt)

Rose polishing a large parrot and rainbow pot with the design sketched in before painting (photo by Tena Garcia).

Pool after a rain.

Aak'u

Imagine

living in one place

for a thousand years,

seeing the rocks

weathering slightly,

walking

on a different layer

of sand.

Imagine

staying and making

of the same clay new bowls,

and houses whose walls

melt slowly in the rains,

replastering, fixing

the flat roofs,

cleaning the cisterns,

hearing the beetles gather dung

and the grasshopper's legs

whirring

as they scrape in the grass.

Imagine windows of mica

and sun still in place,

and watching the hillsides and trees,

changed, and unchanged.

(©1996Carol Snyder Halberstadt)

Mica window.

Outdoor oven.

Rose coiling a pot (photo by Tena Garcia).

Large Parrot and Rainbow pot before firing (photo by Tena Garcia)

The finished Parrot and Rainbow pot, 1997 (Photo by William Frank)

Last pottery from Rose Chino Garcia.

Acoma "Sky City" in New Mexico, is one of the oldest continuously occupied cities in North America. For a thousand years, the people of Aak'u, which has been translated from Keresan as "mesa top" and also as "a place prepared," have been making pottery--vessels of everyday life, of ritual, and of great beauty. During the seventeenth century, potters developed the matte-painted polychrome style, which continues today. Pottery making is learned by children from their parents and grandparents, and is passed on from one generation to the next. In one family, grandmother, mother, uncle, cousin, and grandchild may all be potters. "I remember my mother and I," says Rose Chino Garcia, "we'd sit on the big smooth stones outside our house in the early morning before it got too hot and we'd grind the clay and then the temper. Sometimes all the ladies would sit on the big stones around the plaza, grinding the clay." In her kitchen, the making of pottery still goes on among the activities of daily life.

Three generations--two of potters, and perhaps a third.

Rose Chino Garcia shaping a pot in her kitchen.

Views of Acoma.

Digging the clay: The seeming ease of a finished pot

made in the traditional way belies the enormous amount of work

and skill, of intuition and hard labor, that has gone into its

creation. First, the clay must be mined from the earth at sites

a considerable distance from the village, and often accessible

only on foot. "You can't drive all the way there," says

Rose Chino Garcia. "You have to walk in, and dig out the

clay, and then carry it back to the truck, sometimes a long way,

five miles or more." In its original form the clay is rocky

and slatelike, and large chunks must be broken up to manageable

size. If it was damp when dug, it must be left to dry for many

days in the sun. When dry, it must be cleaned thoroughly by sifting

and winnowing to get rid of all unwanted matter, such as twigs

and pebbles. With a stone, it is crushed and pulverized. Temper,

in the form of clay potsherds, sometimes hundreds of years old,

is hand-ground to a fine powder, and added to the clay to bind,

strengthen, and prevent it from shrinking and cracking. A vessel

made from tempered Acoma clay is very strong, and enables the

potter to make the characteristic thin walls of traditional pottery.

Shaping the pot: It may take many days to create

the proper mixture of ground clay and pulverized potsherd temper.

First blended dry, water is gradually added, and more temper,

until the right consistency is achieved. This knowledge is acquired

by experience and years of working the clay so that it "feels"

right. The pot is then begun by molding the base in a form called

a huditzi, a basket, gourd, or bowl, which supports the

bottom of the vessel. The body is built up by adding coils of

clay that are shaped to the intended form. The length of time

it takes to build the pot varies, as time must pass between the

addition of each coil in order to prevent the sides from falling

in. As the vessel's shape is defined, it is smoothed by hand-scraping

with a gourd, "grown specially for this purpose." After

drying to the right hardness, it is again scraped and smoothed

with a gourd to its desired thinness, and finally sanded smooth

with a stone.

Slip and painting: At this stage, the potter prepares

the slip--a creamy mixture of fine clay and water. A special fine

white kaolin clay is used to make the brilliant white slip of

traditional Acoma pottery, and serves as an ideal "canvas"

for the paints that the potter will use. The clays, vegetable

binders, and mineral pigments for the distinctive Acoma polychrome,

including those derived from certain plants, are dug or gathered

locally, and are ground and mixed by the potter to achieve the

intended colors. Exactly the right mixtures of water, binder,

and pigment must be used, or the colors will either be too powdery

and flake off after firing or be too watery and come out pale.

White slip-covered and polished pot,

hand-smoothed with a stone,

and ready for painting.

The potter brushes on several coats of the white slip, waiting

for it to dry between each coat. After the final coat, it is again

sanded with a stone. The pot is then painted with the specially

prepared pigments, often with a yucca brush, much as it was done

hundreds of years ago. "Painting the fine-lines is hard on

the eyes, you have to rest every so often. You've got to be sure

to rest your eyes every fifteen or twenty minutes" (Rose

Chino Garcia).

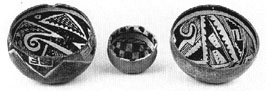

Fine-line pottery by Rose

Chino Garcia.

Fine-line pottery by Rose

Chino Garcia.

Tena Garcia with her painted

pot, ready for firing.

Tena Garcia with her painted

pot, ready for firing.

Firing: The final step is firing, which changes and

often deepens the colors, and bonds them permanently to the clay.

Traditional Acoma pottery is fired at a very high temperature,

which makes the pot stronger. Rose Chino Garcia says that water

tastes better when kept in a pottery jar, "cool and clean."

Since the early 1970s, most traditional potters fire their pots

in an electric kiln, which can maintain the steady high temperature

desired (about 1,873 degrees Fahrenheit; 1,023 degrees Centigrade),

a temperature that can rarely be reached in exposed outdoor pit

firing.

Designs on traditional Acoma pottery include polychrome rainbow bands, birds (parrots or macaws), deer (adapted from the Zuni deer motif, with the distinctive "heartline"), black or dark brown and white abstract stylized adaptations of ancient Anasazi, Mogollon, and Mimbres ware (including geometric shapes, spirals, stepped forms, clouds, dragonflies and butterflies--which are water and rain images). The ancient geometric patterns were developed into the dazzling fine-line designs, which began to appear in their contemporary form in the late 1940s. Hatching symbolizes rain, stepped motifs represent clouds, double dots stand for raindrops, and other symbols stand for mountains, lightning, and thunderclouds. These designs speak of life-giving water, fertility, the life cycle, earth and sky, and the interrelationship of all phenomena.

The future: Pottery making at Acoma, like elsewhere,

is changing. Many potters now work in nontraditional ways--buying

factory-produced mold-made pots with commercial slip, and painting

only the designs by hand, often using commercial paints. This

enables more pottery to be produced faster and to be sold at lower

prices than traditional ware. While most traditional potters use

electric kilns--an adaptation that enhances the pre-kiln Acoma

high-temperature open-pit firing--their pottery is still made

the way it has been for hundreds of years. In digging the clay,

grinding it, blending it with temper, forming and smoothing it

by hand, preparing the pigments, and painting the designs, the

potter speaks with the clay, and the clay answers.

Stamped with an unmistakable cultural style, each traditional

Acoma pot is a unique creation; no two are alike, even from the

hand of the same potter. This pottery--made of clay dug from the

earth, ground, coiled, and shaped by hand, without wheel or mold,

and painted with handmade pigments--does not have the uniformity

or "perfection" of manufactured ware. What it does have

is a life of its own, filled with the breath, energy, and vision

of the potter who made it. At this point in time, such pottery

is still being made at Acoma. It is likely that as economic pressures

increase, there may be fewer potters working in the future, and

even fewer with the time, skill, patience, and love of the art

to create entirely traditional pottery.

Ladder

at Acoma.

Ladder

at Acoma.